From:

The Java platform's garbage collection mechanism greatly increases developer productivity, but a poorly implemented garbage collector can over-consume application resources. In this third article in the JVM performance optimization series, Eva Andreasson offers Java beginners an overview of the Java platform's memory model and GC mechanism. She then explains why fragmentation (and not GC) is the major "gotcha!" of Java application performance, and why generational garbage collection and compaction are currently the leading (though not most innovative) approaches to managing heap fragmentation in Java applications.

Garbage collection (GC) is the process that aims to free up occupied memory that is no longer referenced by any reachable Java object, and is an essential part of the Java virtual machine's (JVM's) dynamic memory management system. In a typical garbage collection cycle all objects that are still referenced, and thus reachable, are kept. The space occupied by previously referenced objects is freed and reclaimed to enable new object allocation.

In order to understand garbage collection and the various GC approaches and algorithms, you must first know a few things about the Java platform's memory model.

JVM performance optimization: Read the series

- Part 1: Overview

- Part 2: Compilers

- Part 3: Garbage collection

- Part 4: Concurrently compacting GC

- Part 5: Scalability

Garbage collection and the Java platform memory model

When you specify the startup option -Xmx on the command line of your Java application (for instance: java -Xmx:2g MyApp) memory is assigned to a Java process. This memory is referred to as the Java heap (or just heap). This is the dedicated memory address space where all objects created by your Java program (or sometimes the JVM) will be allocated. As your Java program keeps running and allocating new objects, the Java heap (meaning that address space) will fill up.

Eventually, the Java heap will be full, which means that an allocating thread is unable to find a large-enough consecutive section of free memory for the object it wants to allocate. At that point, the JVM determines that a garbage collection needs to happen and it notifies the garbage collector. A garbage collection can also be triggered when a Java program calls System.gc(). Using System.gc() does not guarantee a garbage collection. Before any garbage collection can start, a GC mechanism will first determine whether it is safe to start it. It is safe to start a garbage collection when all of the application's active threads are at a safe point to allow for it, e.g. simply explained it would be bad to start garbage collecting in the middle of an ongoing object allocation, or in the middle of executing a sequence of optimized CPU instructions (see my previous article on compilers), as you might lose context and thereby mess up end results.

A garbage collector should never reclaim an actively referenced object; to do so would break the Java virtual machine specification. A garbage collector is also not required to immediately collect dead objects. Dead objects are eventually collected during subsequent garbage collection cycles. While there are many ways to implement garbage collection, these two assumptions are true for all varieties. The real challenge of garbage collection is to identify everything that is live (still referenced) and reclaim any unreferenced memory, but do so without impacting running applications any more than necessary. A garbage collector thus has two mandates:

- To quickly free unreferenced memory in order to satisfy an application's allocation rate so that it doesn't run out of memory.

- To reclaim memory while minimally impacting the performance (e.g., latency and throughput) of a running application.

Two kinds of garbage collection

In the first article in this series I touched on the two main approaches to garbage collection, which are reference counting and tracing collectors. This time I'll drill down further into each approach then introduce some of the algorithms used to implement tracing collectors in production environments.

Read the JVM performance optimization series

Reference counting collectors

Reference counting collectors keep track of how many references are pointing to each Java object. Once the count for an object becomes zero, the memory can be immediately reclaimed. This immediate access to reclaimed memory is the major advantage of the reference-counting approach to garbage collection. There is very little overhead when it comes to holding on to un-referenced memory. Keeping all reference counts up to date can be quite costly, however.

The main difficulty with reference counting collectors is keeping the reference counts accurate. Another well-known challenge is the complexity associated with handling circular structures. If two objects reference each other and no live object refers to them, their memory will never be released. Both objects will forever remain with a non-zero count. Reclaiming memory associated with circular structures requires major analysis, which brings costly overhead to the algorithm, and hence to the application.

Tracing collectors

Tracing collectors are based on the assumption that all live objects can be found by iteratively tracing all references and subsequent references from an initial set of known to be live objects. The initial set of live objects (called root objects or justroots for short) are located by analyzing the registers, global fields, and stack frames at the moment when a garbage collection is triggered. After an initial live set has been identified, the tracing collector follows references from these objects and queues them up to be marked as live and subsequently have their references traced. Marking all found referenced objects live means that the known live set increases over time. This process continues until all referenced (and hence all live) objects are found and marked. Once the tracing collector has found all live objects, it will reclaim the remaining memory.

Tracing collectors differ from reference-counting collectors in that they can handle circular structures. The catch with most tracing collectors is the marking phase, which entails a wait before being able to reclaim non-referenced memory.

Tracing collectors are most commonly used for memory management in dynamic languages; they are by far the most common for the Java language and have been commercially proven in production environments for many years. I'll focus on tracing collectors for the remainder of this article, starting with some of the algorithms that implement this approach to garbage collection.

Tracing collector algorithms

Copying and mark-and-sweep garbage collection are not new, but they're still the two most common algorithms that implement tracing garbage collection today.

Copying collectors

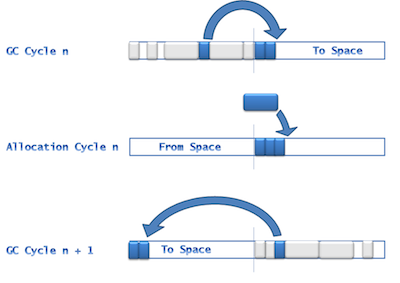

Traditional copying collectors use a from-space and a to-space -- that is, two separately defined address spaces of the heap. At the point of garbage collection, the live objects within the area defined as from-space are copied into the next available space within the area defined as to-space. When all the live objects within the from-space are moved out, the entire from-space can be reclaimed. When allocation begins again it starts from the first free location in the to-space.

In older implementations of this algorithm the from-space and to-space switch places, meaning that when the to-space is full, garbage collection is triggered again and the to-space becomes the from-space, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A traditional copying garbage collection sequence (click to enlarge)

More modern implementations of the copying algorithm allow for arbitrary address spaces within the heap to be assigned as to-space and from-space. In these cases they do not necessarily have to switch location with each other; rather, each becomes another address space within the heap.

One advantage of copying collectors is that objects are allocated together tightly in the to-space, completely eliminating fragmentation. Fragmentation is a common issue that other garbage collection algorithms struggle with; something I'll discuss later in this article.

Downsides of copying collectors

Copying collectors are usually stop-the-world collectors, meaning that no application work can be executed for as long as the garbage collection is in cycle. In a stop-the-world implementation, the larger the area you need to copy, the higher the impact on your application performance will be. This is a disadvantage for applications that are sensitive to response time. With a copying collector you also need to consider the worst-case scenario, when everything is live in the from-space. You always have to leave enough headroom for live objects to be moved, which means the to-space must be large enough to host everything in the from-space. The copying algorithm is slightly memory inefficient due to this constraint.

Mark-and-sweep collectors

Most commercial JVMs deployed in enterprise production environments run mark-and-sweep (or marking) collectors, which do not have the performance impact that copying collectors do. Some of the most famous marking collectors are CMS, G1, GenPar, and DeterministicGC (see Resources).

A mark-and-sweep collector traces references and marks each found object with a "live" bit. Usually a set bit corresponds to an address or in some cases a set of addresses on the heap. The live bit can, for instance, be stored as a bit in the object header, a bit vector, or a bit map.

After everything has been marked live, the sweep phase will kick in. If a collector has a sweep phase it basically includes some mechanism for traversing the heap again (not just the live set but the entire heap length) to locate all the non-marked chunks of consecutive memory address spaces. Unmarked memory is free and reclaimable. The collector then links together these unmarked chunks into organized free lists. There can be various free lists in a garbage collector -- usually organized by chunk sizes. Some JVMs (such as JRockit Real Time) implement collectors with heuristics that dynamically size-range lists based on application profiling data and object-size statistics.

When the sweep phase is complete allocation will begin again. New allocation areas are allocated from the free lists and memory chunks could be matched to object sizes, object size averages per thread ID, or the application-tuned TLAB sizes. Fitting free space more closely to the size of what your application is trying to allocate optimizes memory and could help reduce fragmentation.

More about TLAB sizes

TLAB and TLA (Thread Local Allocation Buffer or Thread Local Area) partitioning are discussed in JVM performance optimization, Part 1.

Downsides of mark-and-sweep collectors

The mark phase is dependent on the amount of live data on your heap, while the sweep phase is dependent on the heap size. Since you have to wait until both themark and sweep phases are complete to reclaim memory, this algorithm causes pause-time challenges for larger heaps and larger live data sets.

One way that you can help heavily memory-consuming applications is to use GC-tuning options that accommodate various application scenarios and needs. Tuning can, in many cases, help at least postpone either of these phases from becoming a risk to your application or service-level agreements (SLAs). (An SLA specifies that the application will meet certain application response times -- i.e., latency.) Tuning for every load change and application modification is a repetitive task, however, as the tuning is only valid for a specific workload and allocation rate.

Implementations of mark-and-sweep

There are at least two commercially available and proven approaches for implementing mark-and-sweep collection. One is the parallel approach and the other is the concurrent (or mostly concurrent) approach.

Parallel collectors

Parallel collection means that resources assigned to the process are used in parallel for the purpose of garbage collection. Most commercially implemented parallel collectors are monolithic stop-the-world collectors -- all application threads are stopped until the entire garbage collection cycle is complete. Stopping all threads allows all resources to be efficiently used in parallel to finish the garbage collection through the mark and sweep phases. This leads to a very high level of efficiency, usually resulting in high scores on throughput benchmarks such as SPECjbb. If throughput is essential for your application, the parallel approach is an excellent choice.

The cost of most parallel collection -- and do consider this, especially for production environments -- is that application threads cannot do any work during a GC, just like with copying collectors. Using a parallel collector that implements stop-the-world collection will have a major impact on response-time sensitive applications, especially if you have a lot of references to trace, which will happen with many live or complex data structures on the heap. (Remember that for mark-and-sweep collectors the time to free up new memory is dependent on the time it takes to trace the live data set plus the time to traverse the heap during the sweep phase.) For a monolithic parallel approach using all resources in parallel, this entire time will be a pause, and that pause corresponds to the entire GC cycle.

Concurrent collectors

A concurrent collector is a much better fit for applications that are sensitive to response time. Concurrent means that some (or most) garbage collection work is performed concurrently with the running application threads. As not all resources are used for GC, you will have the challenge of deciding when to start a garbage collection in order to allow enough time for the cycle to end. You need enough time to trace the live set and reclaim the memory before the application runs out of memory. If the garbage collection doesn't complete in time the application will throw an out-of-memory error. You don't want to do garbage collection all the time because that would consume application resources, thus impacting throughput. It can be extra tricky to keep that balance in very dynamic environments, so heuristics have been designed to determine when to start garbage collection and when to do various GC optimizing tasks and how much at a time, etc.

Another challenge is to determine when it is safe to perform operations that require a complete and true snapshot of the world -- for instance, you need to know when all live objects have been marked, and thus when to switch to the sweep phase. In the monolithic stop-the-world scenario employed by most parallel collectors, thisphase-switching is less tricky because the world is already standing still. But in concurrent implementations it might not be safe to switch phases immediately. For instance, if an application has modified an area that has already been traced and marked by the collector, new or unmarked references may have been touched, which would make them live. In some implementations this situation will put your application at risk for long-time running re-marking loops, potentially making it hard for your application to get new free memory when it needs it.

The takeaway from this discussion so far is that you have numerous options among garbage collectors and GC algorithms, some better suited than others to specific application types and workloads. Not only are there different algorithms, but there are actually different implementations of the various algorithms. So it is wise to be informed about your application's allocation needs and characteristics before simply specifying a garbage collector on the command line. In the next section we'll look at some of the pitfalls of the Java platform memory model -- and by pitfalls I mean places where Java developers tend to make assumptions that lead to worse performance for dynamic production loads, not better.

Why tuning doesn't replace garbage collection

Most Java developers know that there are choices to be made if you want to maximize Java performance. The current variety of JVMs, garbage collectors, and the overwhelming selection of tuning options can lead developers to spend a lot of deployment time on the never-ending task of performance tuning. This has led some to conclude that GC is bad and that tuning so that GC happens infrequently or for just a short time is a successful workaround. But there are risks to doing GC this way.

Consider what it means to tune against specific application needs. Most tuning parameters -- such as allocation rate, object sizes, timing of response-time sensitive tasks, and how fast objects die -- are tuned specifically for the application's allocation rate, such as the test workload at hand. The end result could be either (or both) of these:

- Things that worked during testing fail in production.

- Workload or application changes require you to re-tune the application entirely.

Tuning is something that will always need to be repeated! Concurrent garbage collectors in particular can require a lot of tuning -- especially in production environments. You need the heuristics to match your specific application's needs for the expected worst-case load. The end result becomes a very rigid configuration, leading to a lot of resource waste. This approach to tuning (tuning to eliminate GC) is kind of a Don Quixote quest -- a chase after an imagined enemy with sure-to-lose cause. The fact is that the more you tune your collectors to fit a specific load, the farther you'll be from the dynamic features of a Java runtime. After all, how many applications really have a static load? And how reliably can you really predict for an expected load?

So, what if you didn't focus on tuning? What could you be doing differently to prevent out-of-memory errors and improve response times? The first step toward finding out is to identify the real challenge to Java application performance.

Fragmentation

The real Java performance challenge is not the garbage collector itself; it isfragmentation, and how the garbage collector deals with it. Fragmentation is a state of the heap where free memory is available but not in a big enough consecutive memory space to host a new object about to be allocated. As I mentioned in Part 1, afragment is either a residual space in the Java heap's TLABs, or (more often) a space previously occupied by small objects between longer living objects.

Over time, as an application runs, these fragments of unusable memory will appear all over the heap. In some cases the state will get worse with statically tuned options (like promotion rates, free lists, etc.) that can't keep up with the needs of a dynamic application. Such left-over (fragmented) space can't be used efficiently by an application. If you don't do anything about it you'll eventually end up with back-to-back garbage collections, the garbage collector's attempt to free up memory for a new object allocation request. In the worst-case scenario, even a number of consecutive GCs will not free up memory (too many fragments) and the JVM will be forced to throw an out-of-memory error. You can deal with fragmentation by restarting the application, which makes your heap a new space of consecutivememory mapped to your process, such that you'll be able to allocate objects freely again. Restarting leads to downtime, however, and besides the heap would eventually get fragmented again and you would need to do another restart.

OutOfMemoryErrors, hung processes, and logs showing that your garbage collector is working overtime are all symptoms of a GC struggling to free up memory, and are indicators of a fragmented heap. While some developers seek to resolve fragmentation by simply re-tuning their garbage collector, I argue that we should explore more innovative solutions to the problem of fragmentation before it becomes an issue for GC. The remainder of this article will focus on the two most effective approaches to managing fragmentation: generational garbage collection and compaction.

Generational garbage collection

You may have heard the theory that in production environments most objects die young. Generational garbage collection is an approach to GC that springs from this theory. In a generational garbage collection you basically divide the heap into different spaces (or generations), each covering different ages of objects, where agecould mean the number of GC cycles that the object has survived (that is, how many times it has remained referenced).

When the space for new allocations, also known as young space, nursery, or young generation, is full, objects still referenced within that space are moved into the next generation. Most commonly there are only two generations. Usually generational garbage collectors are one-directional copying collectors, which I discussed earlier. Some more-recent implementations of young generation collectors are parallel collectors. It is also possible to implement different collecting algorithms for young space and old space. If you are using a parallel and/or copying collector then your young generation collectors will be a stop-the-world collector (see earlier explanation).

Old space or old generation hosts the promoted objects that stay referenced for a certain time or certain numbers of young space collections. On occasion, really large objects might be allocated directly into old space, as large objects are more costly to move.

The mechanics of generational GC

In a generational approach, garbage collection happens less frequently in old space and more frequent in young space, where the GC cycle is hopefully shorter and less intrusive. Having a young space can, on rare occasions, lead to more frequent collections in old space, however. Typically, this would happen if you had tuned the nursery size to be too large compared to your current heap size, and if your application's objects tended to survive for a long time (or if you have tuned your promotion rate "incorrectly"). In that case the old generation space would become too small to host all of your long-living objects and the old generation GC would struggle freeing up space to make room for promoted objects. In general, though, by having a generational garbage collector you will gain application performance and latency consistency.

A nice side-effect of having a young generation is that fragmentation is somewhat addressed. Or rather, worst case scenario is postponed. The young, small objects that otherwise might cause fragments are cleaned out of the way. The old space also becomes more compact, because the long-living objects are more tightly allocated as they are moved to the older generation. Over time -- if you run long enough -- the old space will still become fragmented, however. In this case, you will end up with one or several full stop-the-world collections, potentially forcing the JVM to throw anOutOfMemoryError or an error indicating failure to promote. Having a nursery postpones that worst-case scenario, however, and for some applications that is good enough. (In some case it will postpone the full-stop scenario to a point in the application's lifecycle where it doesn't matter anymore.) For most applications having a nursery functions as stop-gap, but it does decrease the frequency of stop-the-world GC and OutOfMemoryError exceptions.

Tuning generational GC

As stated above, with the use of generations comes the responsibility and repetitive work of tuning young generation size and promotion rate for every new version of your application and for every load change. I can't stress enough the trade-off of specializing your runtime: by choosing a fixed number that optimizes for a specific load, you reduce your garbage collector's ability to respond dynamically to change -- and change is inevitable.

My rule-of-thumb for tuning nursery size is that it should be as large as you can make it while ensuring the latency of the young space during stop-the-world collections. (Assuming that the young space is configured to use a parallel collector that is!) Keep in mind, too, that you need to leave enough old space in the heap for long-lived objects -- with margin! Here are some additional factors to consider when tuning a generational garbage collector:

- Most implementations of young space collection will ultimately result in a stop-the-world collection, and the larger the nursery, the longer the associated pause-time will be. So for applications that will be heavily impacted by that GC pause, you should carefully consider how large you want your young space to be.

- You can mix GC algorithms for your heap generations. You could potentially make the young generation GC parallel, while using a concurrent algorithm for old space collection.

- When you see frequent promotion failures it is usually a sign that your old space is fragmented. Promotion failure means that there isn't a large enough space in old space to fit a surviving object from young space. If this happens, consider tweaking the promotion rate (the age tuning option) or make sure your old-space GC algorithm is a compacting one (discussed in the next section) and tune the compaction in a way that fits your current application load. You may also increase the heap size and generation sizes, but doing so could impact the pause times of old space collections further -- remember that fragmentation is inevitable!

- A generational collector work best for any Java application that has many short-lived small objects that will die within their first collection cycle. Generational GC works well to reduce fragmentation in this scenario, mainly by postponing it to a point in the application lifecycle where it may no longer be an issue.

Compaction

Although generational garbage collection postpones the worst-case scenario of fragmentation and OutOfMemoryError, compaction is the only real way of handling fragmentation. Compaction refers to a GC strategy of moving objects together to free up larger consecutive chunks of memory. Compaction thus creates large enough free memory to host new objects.

Moving objects and updating their references is a stop-the-world operation, which comes at a cost to Java performance. (This is true in all cases but one, which I'll discuss in the next article in this series.) The more popular (meaning referenced) an object is the longer the pause time will be. In a case where very little memory is left in the heap and the fragmentation situation is severe -- which usually becomes the case the longer an application runs -- compacting a popular area of the heap may mean seconds of pause time. Compacting the entire heap, which you would do if your system is close to running out of memory, could take tens of seconds.

The pause time for compaction is dependent on how much memory you need to move and how many references you need to update. With a larger heap size, it is statistically more likely that you will have a large number of both live objects with fragments between them and references needing to be updated. The observed average pause time per 1 to 2 GB live data is one second. So in a 4 GB heap, it is likely you will have at least 25 percent live data and will occasionally experience a near one-second pause time.

Compaction and the application memory wall

The application memory wall refers to the maximum heap size you can set before GC pause time (i.e., compaction) interferes with your application enough to break a response-time SLA. Most Java applications today hit their application memory wall at between 4 GB and 20 GB per JVM, dependent on system and application. This is one reason that most enterprise applications are deployed in multiple smaller JVMs instead of using fewer larger (50- to 60-GB) instances. Let's think about this for a minute: Isn't it interesting how much of Java application design and deployment architecture in modern enterprises are defined by the limitations of compaction in the JVM? In this case, we've accepted multi-mini-instance deployments that are costly to manage over time, in order to work around the problem of stop-the-world interruptions needed to deal with fragmented heaps. This is particularly peculiar given how much large-memory capacity we have in modern hardware, and given the ever-increasing demand for more memory access in enterprise Java applications. Why should we settle for just a few gigabytes per instance? Concurrent compaction is an alternate approach that brings down the application memory wall, and will be the topic of my next article in this series.

The observed average pause time per 1 to 2 GB live data is one second. So in a 4 GB heap, it is likely you will have at least 25 percent live data and will occasionally experience a near one-second pause time.

Conclusion: Reflection points and highlights

This article has been an overview of garbage collection, with the goal of refreshing your knowledge about the concepts and mechanics of garbage collection, as well as your awareness of the range of available options. Hopefully it also inspires you to further reading. Most of the options I've discussed are fairly traditional, in that they work implicitly with the limitations of the JVM. In my next article I'll introduce a newer concept, concurrent compaction, which is currently only implemented by Azul's Zing JVM. Concurrent compaction is one of an emerging class of GC techniques that seek to re-imagine the capacity of Java's memory model, particularly in light of today's increased memory and processor capacity.

For now, I'll leave you with an overview of the main points about garbage collection discussed in this article:

- Different garbage collection algorithms and approaches will meet different application needs. Tracing collectors are most commonly used in commercial Java environments.

- Parallel garbage collection uses available resources in parallel to perform GC. This tactic is usually implemented as a monolithic, stop-the-world collector, using all available system resources for a fast GC. Parallel GC thus provides higher throughput, but all application threads must wait until it's finished, which impacts latency.

- Concurrent GC does its work while application threads are still running. The timing of concurrent GC is tricky because it needs to be finished before your application requires memory.

- Generational garbage collection helps postpone fragmentation, but does not eliminate it. Generational GC divides the heap into two spaces, one for allocating young objects and one for objects that (being still referenced) have survived young-space GC. Use a generational collector for any Java application that has many short-lived small objects that will die within their first collection cycle.

- Compaction is the only way to handle fragmentation completely. Most collectors have to perform compaction as a stop-the-world operation. The longer an application runs, the more reference complexity it will have and the more heterogeneous its object-size distribution will be. These factors will result in longer pauses to complete compaction. Larger heap size also impacts the compaction pause because there will likely be more live data and more references to update.

- Tuning can help postpone

OutOfMemoryErrors but the trade-off of too much tuning is rigidity. Be sure that you understand your production-load dynamics as well as your application's object types and reference profile before initiating tuning by trial-and-error. A too-rigid configuration will most likely break under dynamic production loads. Be sure to understand the consequences of a non-dynamic value before setting it.

Next month in the JVM performance optimization series: An in-depth look inside the Concurrent Continuously Compacting Collector (C4) GC algorithm.

зЫЄеЕ≥жО®иНР

еЬ®JVM5.0дЄ≠и∞ГйЕНGarbage Collection еЬ®JVM5.0дЄ≠и∞ГйЕНGarbage Collection еЬ®JVM5.0дЄ≠и∞ГйЕНGarbage Collection

Dive into JVM garbage collection logging, monitoring, tuning, and tools Explore JIT compilation and Java language performance techniques Learn performance aspects of the Java Collections API and get ...

JVMиЗіеСљйФЩиѓѓеЃМеЕ®иІ£жЮРпЉЪеЯЇдЇОзО∞еЃЮж°ИдЊЛ

Garbage Collection Algorithms For Automatic Dynamic Memory Management

The Java Platform, Standard Edition HotSpot Virtual Machine Garbage Collection Tuning Guide describes the garbage collection methods included in the Java HotSpot Virtual Machine (Java HotSpot VM) and ...

JVM жЇРдї£з†Б part07

JVM жЇРдї£з†Б part06

[jvm]жЈ±еЕ•JVM(дЄА):дїО"abc"=="abc"зЬЛjavaзЪДињЮжО•ињЗз®ЛжФґиЧП дЄАиИђиѓіжЭ•пЉМжИСдЄНеЕ≥ж≥®javaеЇХе±ВзЪДдЄЬи•њпЉМињЩжђ°жШѓдЄАдЄ™жЬЛеПЛйЧЃеИ∞дЇЖпЉМж≥®жДПдЄНеЕЙжШѓ System.out.println("abc"=="abc");ињФеЫЮtrueпЉМ System.out.println(("a"+"b"+"c")....

иІ£еЖ≥йЧЃйҐШеЕ≥дЇОtomcatзЪДзЂѓеП£еЉВеЄЄйФЩиѓѓдњ°жБѓ

JVM жЇРдї£з†Бpart1 пЉИзЬЛжИСзЪДдЄКдЉ†иЃ∞ељХ жЬЙ1--9 дЄ™partпЉЙ

WP - Understanding Java Garbage Collection(дЇЖиІ£JavaеЮГеЬЊжФґйЫЖ).pdf WP - C4(C4пЉЪињЮзї≠еєґеПСеОЛзЉ©жФґйЫЖеЩ®).pdf WP - JVM Performance Study(JVMжАІиГљз†Фз©ґдљњзФ®Apache CassandraвДҐжѓФиЊГOracleHotSpot¬ЃеТМAzulZing¬Ѓ).pdf

jvm-npm, йАВзФ®дЇОJVMзЪДеЕЉеЃєCommonJSж®°еЭЧеК†иљљеЩ® JVMдЄКJavascriptињРи°МжЧґдЄ≠зЪДNPMж®°еЭЧеК†иљљжФѓжМБгАВ еЃЮзО∞еЯЇдЇО http://nodejs.org/api/modules.htmlпЉМеЇФиѓ•еЃМеЕ®еЕЉеЃєгАВ ељУзДґпЉМдЄНеМЕжЛђеЃМжХізЪДnode.js APIпЉМеЫ†ж≠§дЄНи¶БжЬЯжЬЫдЊЭиµЦдЇОеЃГзЪД...

дїК姩еЉАжЬЇеПСеЄГз®ЛеЇПпЉМеРѓеК®й°єзЫЃпЉМзЂЯзДґжК•йФЩиѓі8080зЂѓеП£иҐЂеН†зФ®пЉМж≤°еЕ≥з≥ї еП™и¶БжШѓжККеН†зФ®ињЩдЄ™зЂѓеП£зЪДињЫз®ЛжЭАжОЙеН≥еПѓ

JVM жЇРдї£з†Б part09

JVM жЇРдї£з†Б part05

JVM жЇРдї£з†Б part08

Clojure High Performance JVM Programming иЛ±жЦЗazw3 жЬђиµДжЇРиљђиљљиЗ™зљСзїЬпЉМе¶ВжЬЙдЊµжЭГпЉМиѓЈиБФз≥їдЄКдЉ†иАЕжИЦcsdnеИ†йЩ§ жЬђиµДжЇРиљђиљљиЗ™зљСзїЬпЉМе¶ВжЬЙдЊµжЭГпЉМиѓЈиБФз≥їдЄКдЉ†иАЕжИЦcsdnеИ†йЩ§

JVMйЭҐиѓХиµДжЦЩгАВ JVMзїУжЮДпЉЪз±їеК†иљљеЩ®пЉМжЙІи°МеЉХжУОпЉМжЬђеЬ∞жЦєж≥ХжО•еП£пЉМжЬђеЬ∞еЖЕе≠ШзїУжЮДпЉЫ еЫЫе§ІеЮГеЬЊеЫЮжФґзЃЧж≥ХпЉЪе§НеИґзЃЧж≥ХгАБж†ЗиЃ∞-жЄЕйЩ§зЃЧж≥ХгАБж†ЗиЃ∞-жХізРЖзЃЧж≥ХгАБеИЖдї£жФґйЫЖзЃЧж≥Х дЄГе§ІеЮГеЬЊеЫЮжФґеЩ®пЉЪSerialгАБSerial OldгАБParNewгАБCMSгАБParallel...

java hotspotжЇРз†БжѓФиЊГJVMеЃЮзО∞зЪДжАІиГљ ињЩжШѓжИСзЪДжЦЗзЂ†зЪДжЇРдї£з†БгАВ жАОдєИиЈС Java 8еЯЇеЗЖrun-benchmark-java-8.sh Java 11еЯЇеЗЖrun-benchmark-java-11.sh

JVM дЄНеЃЙеЕ®еЃЮзФ®з®ЛеЇПеЇУ ињЩй°єеЈ•дљЬж≠£еЬ®ињЫи°МдЄ≠пЉМе∞ЪжЬ™ж≠£з°ЃеСљеРНгАВ дЄУдЄЇе§ІжХ∞жНЃеИЖжЮРиЃЊиЃ°зЪДйЂШжАІиГљеЇУпЉМеМЕжЛђпЉЪ жШЊеЉПпЉИе†ЖеЖЕеТМе†Же§ЦпЉЙеЖЕе≠ШеИЖйЕНеЩ®еПѓйБњеЕН JVM еЮГеЬЊжФґйЫЖеєґжПРйЂШзЉУе≠Ше±АйГ®жАІ й¶ЖиЧПеЇУ еПѓдї•иґЕеЗЇ 2GB йЩРеИґзЪДжХ∞зїДжКљи±°пЉИеЕЈжЬЙ...